Previous Lives

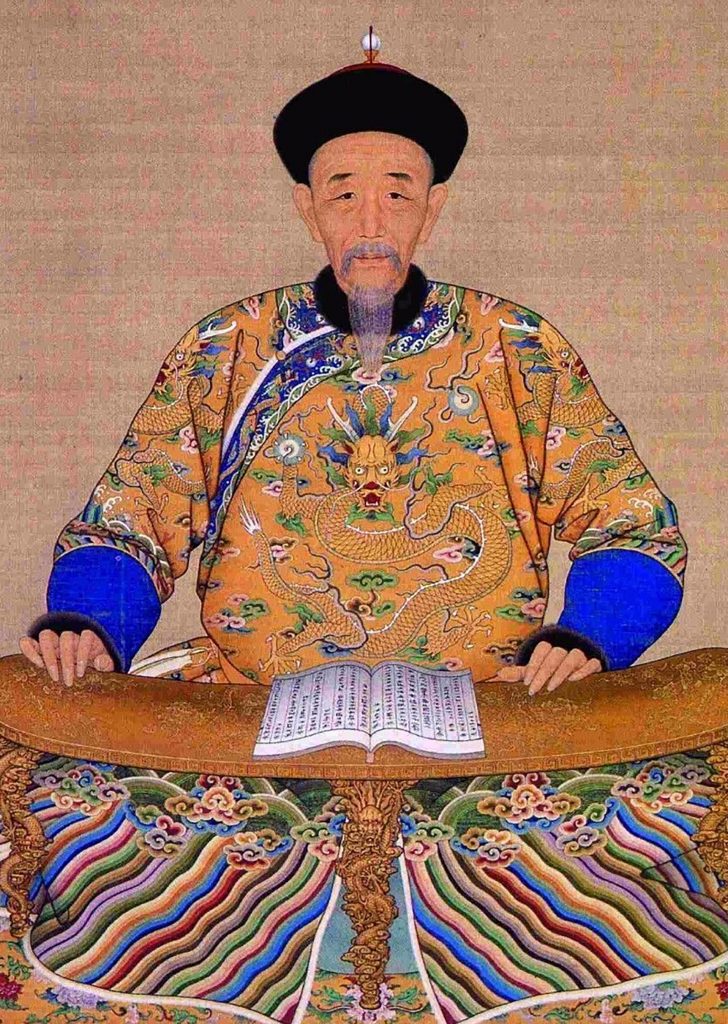

Qing Dharma Ruler

Kangxi Emperor

Of history’s great empires, few have been as politically and culturally significant as the Chinese Empire. The Chinese Empire dominated the East Asian socio-cultural landscape for centuries, influencing everything from religion to art, from geopolitics to music, from language to food. At the heart of it all was the Chinese emperor who commanded and governed millions of people, whose edicts affected every aspect of his subjects’ lives. The emperors were vast and varied; some were inventors and innovators for example, while others were master builders or accomplished military tacticians. One emperor however, was known to be a cultural and religious icon, widely praised for his benevolence and foresight, and beloved for his humility and selfless nature: the Qing Emperor Kangxi.

Of history’s great empires, few have been as politically and culturally significant as the Chinese Empire. The Chinese Empire dominated the East Asian socio-cultural landscape for centuries, influencing everything from religion to art, from geopolitics to music, from language to food. At the heart of it all was the Chinese emperor who commanded and governed millions of people, whose edicts affected every aspect of his subjects’ lives. The emperors were vast and varied; some were inventors and innovators for example, while others were master builders or accomplished military tacticians. One emperor however, was known to be a cultural and religious icon, widely praised for his benevolence and foresight, and beloved for his humility and selfless nature: the Qing Emperor Kangxi.

Kangxi came to the throne amidst Dharma beginnings after his father, the Qing Emperor Shunzhi, quietly abdicated after the birth of his son. Fearing disgrace would befall the young Qing dynasty, the empress announced the sudden death of her husband who had, in fact, become a monk in Wu Tai Shan, the abode of Manjushri, the Buddha of Wisdom. Kangxi was just six at the time and still too young to rule; until he came of age, a regent would rule in his stead.

After years of war and chaos, Kangxi’s ascension to the throne brought about much needed peace and stability. The young emperor proved to be a masterful politician, minimising plotting in his court by encouraging his officials to focus on literary works. Kangxi’s support and encouragement led to the compilation of vast encyclopedias and the Kangxi Chinese dictionary. He showed a similarly skilled hand when dealing with his army, taking as much care with his rank soldiers as he did in commanding his generals during military campaigns.

Kangxi’s single-minded focus on improving his country won the respect and hearts of his subjects. A tireless worker, the emperor was known to stay up late into the night to ensure documents requiring his approval were ready for dispatch the following morning. As a result of his dedication to his kingdom, Kangxi was known to have fewer concubines than other Qing Emperors; he eschewed spending time on himself in favour of serving his people.

Under Kangxi’s patronage, fueled by his own personal interest in the teachings, the Dharma flourished throughout China. Thanks to his early exposure to Buddhism, the emperor was fascinated with the Buddha’s teachings, especially that of the Tibetan Buddhist faith. He became an important patron of the Dharma, not only as a sponsor but as a practitioner as well; unlike many other emperors, Kangxi’s practice of humility meant he never carried himself with the arrogance of an emperor.

As part of his pursuit of spiritual practice, Kangxi visited Wu Tai Shan six times. On some of these trips, he sponsored ceremonies and made offerings dedicated to the longevity of the Imperial Family. Kangxi thus began the tradition of Tibetan lamas engaging in pujas in order to lengthen the lives of loved ones, a practice which continues up till this day.

The emperor also used his immense wealth to sponsor spiritual literature, including the writing of the Tibetan Dragon Sutra using gold ink. It is a text that documents the concise Prajnaparamita teachings and is still preserved today. During his reign, the Tibetan scriptural canon, the Kangyur, was published from woodblocks, first in Tibetan and then in Mongolian. Kangxi was also a sponsor of His Holiness the 7th Dalai Lama’s entrance into Kumbum Monastery.

But perhaps the most visible signs of Kangxi’s Dharma patronage are the many Buddhist temples and pilgrimage sites in China, Tibet and Mongolia that he was involved with. He was directly responsible for the establishment, preservation and restoration of these spiritual powerhouses, many of which still exist today. For example, Gaden Sumtseling Monastery which was built by His Holiness the 5th Dalai Lama, was sponsored by Kangxi, who would frequently visit the site to personally oversee its construction. Later, nearly four tonnes of silver that Kangxi bequeathed in his will was used to construct Amarbayasgalant Monastery in Mongolia.

Given his benevolent nature and extensive patronage of the Dharma, many lamas and masters have declared that Kangxi was more than just a secular emperor, stating that he was an emanation of no less than the Bodhisattva Manjushri. Prior to his passing, Kangxi had decreed that even in death, his final resting place should reflect the manner in which he lived his life. Thus, after passing at the age of 61, the Dharma Emperor was laid to rest in a humble and simple tomb, carved with images of the 35 Confessional Buddhas and other Buddhist deities, an enduring testament of his deep faith.

Kangxi proved that it is possible to rule with wisdom and in accordance with the Buddhist teachings of kindness and discipline, without the mention of the word Buddhism. He was, in fact, so forward-thinking that he even gave Christian missionaries permission to build churches and propagate their religion. His reign was an age of progress and prosperity, ushering in an era of cultural, economic, scientific and spiritual flourishing. It is a testament to his scholarship, political astuteness and selfless behaviour that centuries after his passing, Kangxi’s name continues to elicit respect and he remains known as one of the greatest emperors to have ever ruled.